Key Findings

We had originally set out knowing that we wanted to make museums more accessible, but we weren’t sure how or for whom. After gathering data, we have found that there is much to be asked about how museums can be more accessible for people of color. After two contextual inquiries with Williams College students and two interviews with WCMA staff members, we have been able to identify a strong need for museums to center people of color and their narratives, as well as several examples of how museums (and WCMA) have grappled with issues of accessibility in the past. Our data shows a sense of distrust that students of color may have in museums generally, as well as the ways in which museums today are working to foster discussion and incorporate community feedback.

Contextual Inquiry and Interview Results

Contextual Inquiry 1: Williams College Student We conducted a contextual inquiry with a Williams College student at WCMA. The student has no expertise in art or art museums and does not consider herself “an art person.” We explained that we were in the data collection phase of a design project and that we were interested in the theme of “museums for all,” but we stressed that we were not at a point where we were being concrete about what that meant. The contextual inquiry went really well in that the interviewee was very willing to share her thoughts and opinions throughout the hour-long session, and she provided us with a lot of emotional data. She frequently told us how she was feeling and what had caused her to feel that way. It was from this contextual inquiry that we got a strong sense that museums may not be accessible to people of color for a number of reasons, and we were also able to gather concrete data that illustrated the nature of the discomfort that is resultant of this inaccessibility as well as specific points of criticism to how the museum was representing people of color and people of color issues.

Interview 1: WCMA Staff We conducted an interview with a curator from WCMA at WCMA. She has extensive background in the incorporation of art into the classroom, specifically helping students and professors engage with artwork in museums. We conducted a semi-structured interview, having brought a list of preliminary questions for her. As the conversation unfolded, we asked other questions pertaining to the matter of making museums more accessible for people without revealing that our focus is people of color. She herself stated that museums are not “open for all” and that this is a conversation that should be taking place in museums. Moreover, Asking her questions about her background and observations in museums is extremely helpful for our project since she revealed information that may not be obvious to museum visitors and us, the interviewers. She helped shed a light on new perspectives since WCMA staff are the ones who interact with museum visitors the most (besides art). She was really open to not only talk about herself but also her mother who was a curator at LACMA. Her initiatives to foster discussions about art and redefining who museums should target has given us another puzzle piece to work with.

Contextual Inquiry 2: Williams College Student We conducted a contextual inquiry at WCMA with a current Junior at Williams College with not much experience in art or with museums. During the contextual inquiry, we followed her throughout WCMA and observed her examining various exhibits. We asked questions when appropriate. Throughout the contextual inquiry she repeatedly expressed that she does not go to museums often because the exhibits ‘don’t make sense.’ On multiple occasions she expressed that art that has many different interpretations and this fact makes them inaccessible, for this particular CI subject. For some exhibits, the topic of the exhibit or not knowing about the origin of topics make it difficult to understand because she doesn’t know how/why they came to be in the museum. The biggest take away from this contextual inquiry is that some visitors, especially ones with no prior experience being in museums, feel intimidated by the exhibits, especially when there is uncertainty and controversy in interpretation.

Interview 2: WCMA Staff We conducted a semi-structured interview with another WCMA staff person as well. Her work involves public, student, and academic/faculty engagement with the museum as well as interpretation. Here, interpretation refers to the design of exhibits with a sensitivity toward the story the museum is trying to tell and a critical lens on the way they tell it. We began the interview by asking her about her role at the museum and how it has changed overtime. We then transitioned to a conversation focused on accessibility in museums in general, not revealing that our focus was on accessibility for people of color. Our interviewee shared a lot of insight with us about accessibility issues in museums in general. She highlighted those with hearing, seeing, or mobility impairments and also addressed the issue of intellectual/academic inaccessibility. She also considered the interpretation of exhibits to be an important area of (in)accessibility which the museum designs iteratively for. That is, she described a process of tweaking museum spaces based on feedback gathered explicitly, observations of visitors by staff, and other methods of evaluation. This interview was very helpful just in getting a sense of the methods of data collection, iterative design, and evaluation WCMA employs. The interviewee was also able to share with us how WCMA goes about fostering discussion and addressing community feedback. The biggest takeaway from this interview is that we realized that there is a disconnect between expressing/conveying these discussions to the general public. It will be worthwhile to investigate if there is a way to improve accessibility and comfort in a museum by somehow conveying the topics and conversations that are already taking place at WCMA.

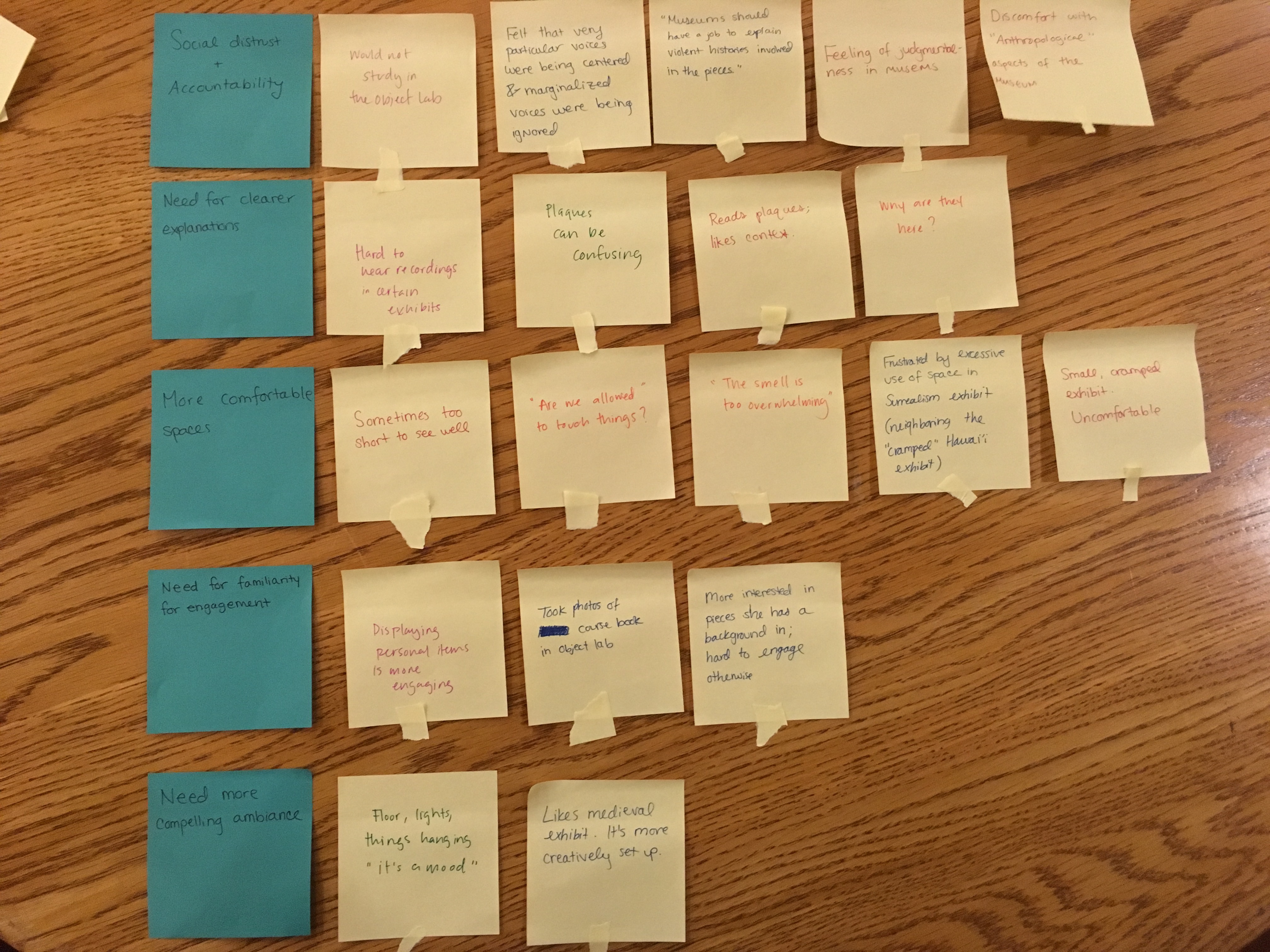

Building An Affinity

High Level Themes

- A need for accountability that has resulted from social distrust of museums

- Museums, specifically labels and audio recordings need clearer explanations

- Users are categorizing museums as uncomfortable spaces, so there is a need to make museums more comfortable for users

- People are more likely to engage with art if there is a sense of familiarity present

- People are also more likely to engage with art if there is a compelling ambiance

Do these themes, problems, and practices suggest tasks important to design for?

Yes, from the affinity diagram we can see that the tasks important for our design include:

- Centering the narratives of people of color / challenging the privileging of dominant voices

- Figuring out how museum spaces can be more comfortable and less overwhelming, while also making them more compelling

- Helping users feel connected to artworks, especially when they do not identify as “art people”

Process for identifying these themes

Creating an affinity diagram was no simple task. We first began by looking back at the data we collected from our contextual inquiries and interviews. We only used two different color post it notes for this affinity diagram. We did not want to categorize data based on the different people we interviewed; instead we took a holistic approach. We started off by writing data points– such as quotes, comments, and observations– on sticky notes. We then began to match the pile of post it notes by lining them up in a row. We then collectively named each row.

Task Analysis

Who is going to use the design? We are designing primarily for people of color who do not feel comfortable in museum spaces. This discomfort may stem from the feeling that PoC voices are not centered in museum exhibits, a lack of PoC representation, or the ways in which issues relating to PoC are (or are not) addressed by the museum.

What tasks do they now perform? They visit the museum and peruse the works. The time spent with each exhibit can depend significantly on their ability to relate to the gallery. They may also partake in conversation about the museum; we found that some of our subjects discussed the exhibits they felt strongly about with friends outside of WCMA.

What tasks are desired? There is a clear desire to see PoC narratives and experiences centered. It seems that what people want is for museums to be more critical about their representation of PoC and PoC issues. We perceive a sense of distrust in the way museums handle PoC narratives and we want our intervention to be something that both addresses the criticisms PoC are expressing and provides an alternative or supplemental mode of engagement, thereby creating opportunities for PoC to still have positive experiences in the museum. This might mean providing alternative context and critique for exhibits, fostering conversation about them, or even just making visible the conversations that are ongoing.

How are the tasks learned? People learn how to engage with art museums through a process of socialization. Visitors perceive a sort of museum culture that dictates how they feel they are expected to behave in museums. Additionally, exposure to topics relevant to the museum subject matter from class (not necessarily art or art history class) also help visitors engage with the art.

Where are the tasks performed? The museum itself is an important space as this is where people see the art in person, do much of the learning/reading about the works, and get a general sense of how the museum as an institution is engaging with the subject matter. Conversations about the museum may happen outside of the museum or at WCMA-facilitated discussions.

What is the relationship between the person and data? Our design is meant to provide an alternative or supplementary mode of engagement for people of color that directly centers PoC subjectivities in the museum. Therefore, we want users to be able to access conversations, critiques, or supplementary info that does this. In this way, the data is communal; users are meant to know that other people care about this content and want to share it.

What other tools does the person have? At the moment, other than talking face to face with other people or visiting museum run discussions, users seem to not have many other tools to communicate reactions, feelings and conversations of discomfort. How do people communicate with each other? In our design, people communicate with each other by commenting and expressing their opinions and feelings of discomfort in a setting that is accessible by all users at all times.

How often are the tasks performed? These tasks can be completed as often as users visit the museum. What are the time constraints on the tasks? There is no general time constraint on the tasks. Visitors who go to WCMA and spend time at exhibits go at their leisure and spend as much time with art as they would like. However as mentioned before, the time spent with each exhibit can depend significantly on their ability to relate to the gallery.

What happens when things go wrong? In our design, when things go wrong and users are unable to share or communicate their feelings or interpretations, users should be able to report it to the project designers. As curators of a potential forum for discussion, the designers will ensure that conversations and content is accessible to all potential users and all users can contribute appropriate material.